Learn to draw cartoons: Lesson 4 - The head in detail

ABOUT THIS POST

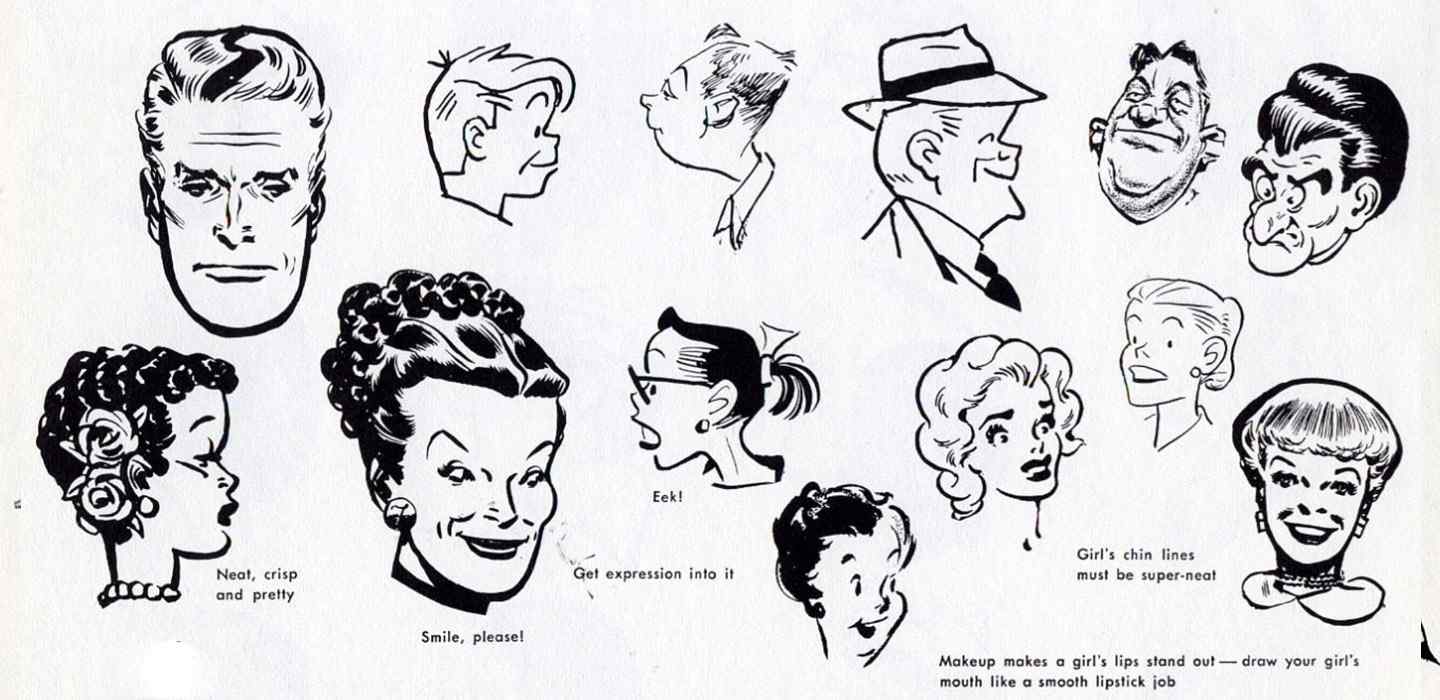

In Lesson One you studied the simple comic head, drawing it from a toy balloon. Now you are ready to consider the comic head in a more detailed manner. Of course, the other parts of the body must fit in with the type of head you draw. But remember that the observer’s attention is first focused on the face and head. Hence, these parts are all-important. A mere exaggeration of features does not always convey character. There must be mobility in the features and feeling that a human being is pictured by the lines representing the face, no matter how comic or grotesque the face may be. On the opposite page is shown the head of Apollo, conceded to be the most finely proportioned of the Greek gods. Surrounding Apollo are heads that are about as different in beauty and symmetry from him as possible. Yet these comic heads and faces are as alive as that of the perfect Apollo, and perhaps convey more character. Moreover, they are not ugly in an unpleasant sense. A face can be interesting, homely comic, crazily proportioned, and not be ugly. Ugliness is something that should be avoided in cartooning. It takes experience to know what is grotesque without being ugly.

A Style Develops

Cartooning the head

We cartoon heads by simplifying their out• lines and exaggerating those features which will best show the type we want to draw -handsome hero, villain, highbrow, lowbrow, etc. By exaggeration we mean making the features much larger or smaller than in real life. However, dan’t exaggerate the size of ALL the features or you’ll end up merely with an unfunny oversized face. If, for instance, you wish to emphasize a large nose, make the eyes and/or the mouth small. Then, by contrast, the nose will seem even larger. By the same token, a big mouth will appear larger if the nose is small. To help get across your character’s mood you can also exaggerate his facial expression

The head and neck

If you balanced an ostrich egg on a tin can you’d have a good representation of the basic forms of the head and neck and their relationship to each other in their normal position. However, the head can assume many other attitudes: it can tilt forward, backward, or sideways as well as turn from side to side. Combine these actions with the appropriate facial expressions and you can reveal your characters’ feelings much more clearly and emphatically. A pugnacious expression, for example, becomes even more pugnacious if the head juts forward belligerently. A startled or frightened expression is heightened by a backward thrust of head and neck. These and similar head gestures will give life and animation to your cartoon figures. When you’re faced with a problem of expression, it’s a good idea to act out the situation or emotion in front of a mirror. Study the attitudes your head assumes with various facial expressions. It often helps to exaggerate these head gestures -but always base your exaggeration on reality.

Basic Expressions

Here you see a variety of features that express some of the human emotions. Note that the ball-type nose has little to do with the expression. When showing “vanity,” the nose is turned up to emphasize the hauteur of the subject, but generally the nose has little to do with expression because it is immovable unless the whole head is turned. The eyes and the mouth are keys to changing moods. Raised eyebrows, the frown (a line between the eyebrows), the droopy lids, the lowered eyebrows, the,,upright narrow circles with the eyeballs in the center, the closed eyes – all help you quickly get across the expression you want.

The mouth – accented by cheek and lip lines – is an equally vital part of any expression. The teeth showing from one side; the round, open mouth, the laughing mouth with the raised corners, the puckered mouth with a suggestion of the lower lip; the lopsided mouth; the large mouth; the small mouth – all have their place in the great cycle of human emotions. Constant practice – and an occasional peek into your mirror – will bring you to a point where these devices will become automatic in your work. They will immediately come to your mind – and hence the tip of your pen or pencil – as soon as you want a character to show an emotion in your cartoon creation.

The comic eye

The comic nose

There’s something fundamentally funny about a nose. It sticks into other people’s business – it smells a rat – it makes a sound like a foghorn. Best of all, you can use it very effectively to create character. Large or small, a nose is a cartoonist’s delight.

The human schnozzle has only four basically different shapes. However, by combining the characteristics of one· group with those of another and adding a dash of exaggeration you can come up with countless comic variations. You can use almost any outlandish shape, as long as it looks as though your character can breathe through it. Here are a few of the thousands of possibilities. Practice them – and have the fun of creating some of your own.

The mouth and chin

The mouth smiles, grins, snarls and hollers. You will probably find your own mouth moving as you draw one on a character -let it. It means that you are getting a little feeling into your drawing. Here again, simplify. Don’t try to draw a whole line of separate crockery for teeth in an open mouth where’a, single line will do. The shadow of the lower lip, cheek lines, etc;.; are up to you: will they help the character you are drawing, or will they clutter it up? Na tu rally, in the adventure-type of characters, the mouth must have more realism.

The chin is an important part of the face. With it you can indicate weakness, strength or weight. The chin also gives you a great chance to be funny – it can be exaggerated in size or left out altogether. Just remember that the chin, mouth and nose should all more or less fit together. They have an important bearing on character.

The ear

Drawing hair on the head

When you draw hair on the comic head, remember this very important point – be sure to draw the outline of the top of the head in pencil before you put hair on it. Many beginners draw the face and then pile a stack of hay on top for hair. They forget that there is a solid head under the hair, and create a head which is all out of proportion. When drawing a character for a strip or a continued feature, you want the head to look the same every time. To get the same shaped head – pencil the shape under the hair every time.

Hair to indicate type

Hair, or the lack of it, can indicate the type of character you wish to draw. Sophisticate or yokel, glamour type or spinster – by their hair you shall know them – and draw them. Hair can be funny – or serious. Learn to use it.When drawing hair, it sometimes helps to change from pen to brush – or from a Gillott 170 to a Gillott 290. Hair is flexible and demands a flexible line. Don’t use a thousand lines where three would do the trick. Try to make it appear to grow from the scalp by “combing” it with the pen or brush, letting the ink strokes follow the fl.ow of the hair strands.

Hair on the face

Everyone is intrigued by a beard. Look at the posters on the fences in you/ town. If the faces do not have a mustache or beard drawn on them, they are likely to have one by the time you finish this lesson! Like the hair, beards and mustaches can indicate character and type. They can make a figure look domineering or downtrodden, diabolic or divine. Styles in mustaches and beards seem to grow funnier as they vary – maybe because hair on the face seems so unnecessary and futile. Futility is a basic comic factor in human nature. Treat the beard or mustache the same as the hair: don’t overdraw, and keep your lines sharp and clean. Here are a few suggestions:

Putting the parts together

You’ve seen how to construct the eyes, nose, mouth, chin and ears of a comic character and how to decorate the result with hair. Using the balloon head of Lesson I, now is the time to experiment and practice the business of putting the parts together. This should be fun and if you’re going to be a cartoonist, this experimenting will continue for a lifetime. Combining features is an endless pastime – the results are endlessly surprising. Most of the characters you develop will wind up in the waste basket. This is a natural state of affairs and comes under the heading of experience. Some of them, however, will smile or smirk or glare up at you from the paper and set your mind working along new and delightful lines. These are characters and, what’s more, they’re your characters – your own personal, beautiful babies. They make life worth living. Keep that pencil of yours searching for them. To give you concrete examples of how the combining process works, here are some examples by the faculty. Each man has started with a penciled balloon, placed the features and inked in the drawing. No two are alike; they vary from comic to realistic, but the process they used was the same. The results are good, solid cartoon characters.

Learn to Draw Cartoons is a series of articles based on the Famous Artist Cartoon Course book, now in public domain. This lesson artists are: Rube Goldberg, Milton Caniff, Al Capp , Harry Haenigsen Willard Mullin, Gurney Williams , Dick Cavalli , Whitney Darrow, Jr. Virgil Partch, Barney Tobey.

Click here for Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 Part 5